In theory, probability distribution and expected values are the reflection of measure and integration theory. Many continuous probability distribution

where Lebegues sense and the second integration Lebesgue–Stieltjes sense.

Generally, the probability of any event

And it is a begin to the tour of probabilistic programming. It also may provide some mathematical understanding of the machine learning model. It is more useful in some simulation problem. Additionally, we will introduce some Monte Carlo methods or stochastic simulation.

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) is a family of algorithms used to produce approximate random samples from a probability distribution too difficult to sample directly. The method produces a Markov chain that whose equilibrium distribution matches that of the desired probability distribution. Since Markov chains are typically not independent, the theory of MCMC is more complex than that of simple Monte Carlo sampling. The practice of MCMC is simple. Set up a Markov chain having the required invariant distribution, and run it on a computer.

- http://www.mcmchandbook.net/

- An Introduction to MCMC for Machine Learning

- The Markov Chain Monte Carlo Revolution by Persi Diaconis

- https://skymind.ai/wiki/markov-chain-monte-carlo

- Markov chain Monte Carlo @Metacademy

- http://probability.ca/jeff/ftpdir/lannotes.4.pdf

- Markov Chains and Stochastic Stability

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo Without all the Bullshit

- Foundations of Data Science

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo: innovations and applications in statistics, physics, and bioinformatics (1 - 28 Mar 2004)

- Advanced Scientific Computing: Stochastic Optimization Methods. Monte Carlo Methods for Inference and Data Analysis by Pavlos Protopapas

- Radford Neal's Research: Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- Computational Statistical Inference for Engineering and Security Workshop: 19th September 2019

- MCMC Coffee

- MCMClib

- https://twiecki.io/

- https://www.seas.harvard.edu/courses/cs281/papers/neal-1998.pdf

- https://www.seas.harvard.edu/courses/cs281/papers/roberts-rosenthal-2003.pdf

- https://twiecki.github.io/blog/2015/11/10/mcmc-sampling/

- PyMC2

- https://cosx.org/2013/01/lda-math-mcmc-and-gibbs-sampling

- https://chi-feng.github.io/mcmc-demo/

- https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~sinclair/cs294/

- https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~aldous/RWG/Book_Ralph/Ch11.html

- http://web1.sph.emory.edu/users/hwu30/teaching/statcomp/statcomp.html

- https://www.cs.ubc.ca/~arnaud/stat535.html

- http://www.gatsby.ucl.ac.uk/vbayes/vbpeople.html

Gibbs sampling is a conditional sampling technique. It is known that

Algorithm: Gibbs Sampling

- Initialize ${{z}i^{(0)}}{i=1}^{n}$;

- For

$t=1,\dots,T$ :- Draw

$z_{1}^{(t+1)}$ from$P(z_{1}|z_{2}^{\color{green}{(t)}},z_{3}^{(t)},\dots, z_{n}^{(t)})$ ; - Draw

$z_{2}^{(t+1)}$ from$P(z_{2}|z_{1}^{\color{red}{(t+1)}},z_{3}^{(t)},\dots, z_{n}^{(t)})$ ; -

$\vdots$ ; - Draw

$z_{j}^{(t+1)}$ from$P(z_{j}|z_{1}^{\color{red}{(t+1)}},\dots, z_{j-1}^{\color{red}{(t+1)}}, z_{j+1}^{(t)}, z_{n}^{(t)})$ ; -

$\vdots$ ; - Draw

$z_{n}^{(t+1)}$ from$P(z_{n}|z_{1}^{\color{red}{(t+1)}},\dots, z_{j-1}^{\color{red}{(t+1)}}, z_{n-1}^{\color{red}{(t+1)}})$ .

- Draw

The essence of Gibbs Sampling is integrals as iterated integrals.

- https://metacademy.org/graphs/concepts/gibbs_sampling

- https://metacademy.org/graphs/concepts/gibbs_as_mh

The Metropolis–Hastings algorithm involves designing a Markov process (by constructing transition probabilities) which fulfills the existence of stationary distribution and uniqueness of stationary distribution conditions, such that its stationary distribution

The approach is to separate the transition in two sub-steps; the proposal and the acceptance-rejection. The proposal distribution acceptance ratio

The Metropolis–Hastings algorithm thus consists in the following:

- Initialise

- Pick an initial state

$x_{0}$ ; - Set

$t=0$ ;

- Pick an initial state

- Iterate

- Generate: randomly generate a candidate state

$x'$ according to${\displaystyle g(x'|x_{t})}$ ; - Calculate: calculate the acceptance probability

$A(x',x_{t})=\min(1, \frac{P(x')}{P(x)} \frac{g(x|x')}{g(x'|x)})$ ; - Accept or Reject:

- generate a uniform random number

${\displaystyle u\in [0,1]}$ ; - if

${\displaystyle u\leq A(x',x_{t})}$ , accept the new state and set${\displaystyle x_{t+1}=x'}$ ; - if

${\displaystyle u>A(x',x_{t})}$ , reject the new state, and copy the old state forward$x_{t+1}=x_{t}$ ;

- generate a uniform random number

- Increment: set

${\textstyle t=t+1}$ ;

- Generate: randomly generate a candidate state

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Metropolis%E2%80%93Hastings_algorithm

- https://metacademy.org/graphs/concepts/metropolis_hastings

http://www.kmh-lanl.hansonhub.com/talks/valen02vgr.pdf

MCMC Using Hamiltonian Dynamics, Radford M. Neal said

In 1987, a landmark paper by Duane, Kennedy, Pendleton, and Roweth united the MCMC and molecular dynamics approaches. They called their method “hybrid Monte Carlo,” which abbreviates to “HMC,” but the phrase “Hamiltonian Monte Carlo,” retaining the abbreviation, is more specific and descriptive, and I will use it here.

- The first step is to define a Hamiltonian function in terms of the probability distribution we wish to sample from.

- In addition to the variables we are interested in (the "position" variables), we must introduce auxiliary "momentum" variables, which typically have independent Gaussian distributions.

- The HMC method alternates simple updates for these momentum variables with Metropolis updates in which a new state is proposed by computing a trajectory according to Hamiltonian dynamics, implemented with the leapfrog method.

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1206.1901.pdf

- Hamiltonian Monte Carlo

- Roadmap of HMM

- https://chi-feng.github.io/mcmc-demo/app.html#HamiltonianMC,banana

- http://slac.stanford.edu/pubs/slacpubs/4500/slac-pub-4587.pdf

- http://www.mcmchandbook.net/HandbookChapter5.pdf

- https://physhik.github.io/HMC/

- http://arogozhnikov.github.io/2016/12/19/markov_chain_monte_carlo.html

- https://theclevermachine.wordpress.com/2012/11/18/mcmc-hamiltonian-monte-carlo-a-k-a-hybrid-monte-carlo/

Hamiltonian dynamics are used to describe how objects move throughout a system. Hamiltonian dynamics is defined in terms of object location

To relate

Since joint distribution factorizes over

Given initial state

- set m=0

- repeat until m=M

-

set

$m\leftarrow m+1$ -

Sample new initial momentum

$p_0 \sim N(0,I)$ -

Set

$x_m\leftarrow x_{m−1}, x^{\prime}\leftarrow x_{m−1}, p^{\prime}\leftarrow p_0$ -

Repeat for

$L$ steps- Set

$x^{\prime}, p^{\prime}\leftarrow Leapfrog(x^{\prime},p^{\prime},\epsilon)$

- Set

-

Calculate acceptance probability

$α=\min(1,\frac{exp(U(x^{\prime})−(p′.p′)/2)}{exp(U(x_m−1)−(p_0.p_0)/2)})$ -

Draw a random number

$u \sim Uniform(0, 1)$ -

if

$u\leq \alpha$ then$x_m\leftarrow x^{\prime},p_m\leftarrow p^{\prime}$ .

-

Leapfrog is a function that runs a single iteration of Leapfrog method.

- http://khalibartan.github.io/MCMC-Hamiltonian-Monte-Carlo-and-No-U-Turn-Sampler/

- http://khalibartan.github.io/MCMC-Metropolis-Hastings-Algorithm/

- http://khalibartan.github.io/Introduction-to-Markov-Chains/

- http://khalibartan.github.io/Monte-Carlo-Methods/

- https://blog.csdn.net/qy20115549/article/details/54561643

- http://arogozhnikov.github.io/2016/12/19/markov_chain_monte_carlo.html

Slice sampling, in its simplest form, samples uniformly from underneath the curve

- Choose a starting value

$x_0$ for which$f(x_0)>0$ . - Sample a

${y}$ value uniformly between$0$ and$f(x_0)$ . - Draw a horizontal line across the curve at this

$y$ position. - Sample a point

$(x,y)$ from the line segments within the curve. - Repeat from step 2 using the new

$x$ value.

The motivation here is that one way to sample a point uniformly from within an arbitrary curve is first to draw thin uniform-height horizontal slices across the whole curve. Then, we can sample a point within the curve by randomly selecting a slice that falls at or below the curve at the x-position from the previous iteration, then randomly picking an x-position somewhere along the slice. By using the x-position from the previous iteration of the algorithm, in the long run we select slices with probabilities proportional to the lengths of their segments within the curve.

- https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.aos/1056562461

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Slice_sampling

- http://www.probability.ca/jeff/java/slice.html

The general idea behind sampling methods is to obtain a set of samples

Let

The algorithm of importance sampling is as following:

- Generate samples

$\vec{X}_1,\vec{X}_2,\cdots,\vec{X}_n$ from the distribution$q(X)$ ; - Compute the estimator $\hat{\mu}{q} =\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}\frac{f(\vec{X_i})p(\vec{X_i})}{q(\vec{X_i})}$

See more in

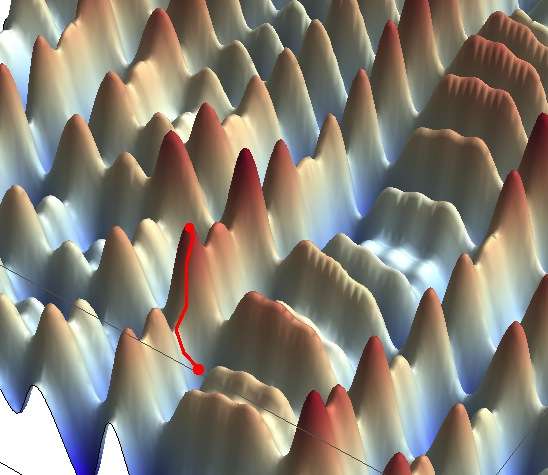

Simulated annealing is a global optimization method inspired by physical annealing model.

If

If we identify a distribution

SO we can minimize one objective function

- Move from

$x_i$ to$x_j$ via a proposal:- If the new state has lower energy, accept

$x_j$ . - If the new state has higher energy, accept

$x_j$ with the probability$$A=\exp(-\frac{\Delta f}{kT}).$$

- If the new state has lower energy, accept

The stochastic acceptance of higher energy states allows our process to escape local minima.

The temperature

And we ensures

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simulated_annealing

- http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SimulatedAnnealing.html

- http://rs.io/ultimate-guide-simulated-annealing/

- http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs.cmu.edu/project/anneal/www/tech_reports.html

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/simulated-annealing/

- https://am207.info/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301290395_Lecture_on_Simulated_Anealing